Periods

Periods in Erwin Bowien's life

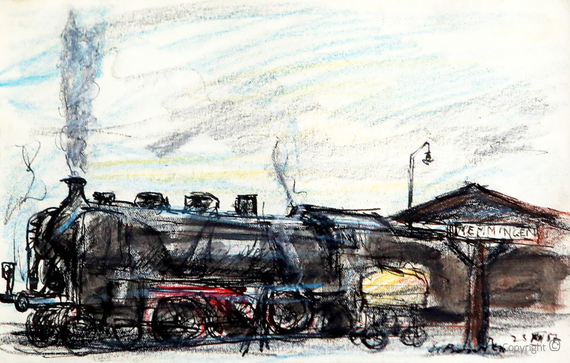

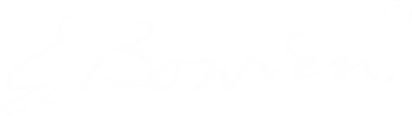

Impressions from Erwin Bowien's retrospective in the Museum on Lindenplatz in Weil am Rhein. The exhibition occupied the Complete Museum for almost a year between 2013 and 2014. On the occasion of this show, elaborate buildings were also created, including a diorama of the Allgäu village "Kreuzthal-Eisenbach" between Kempten and Isny, in which the artist was during the War hid.

The Bowien family

The Bowien family - a parental home between Switzerland and the Markgräfler Land

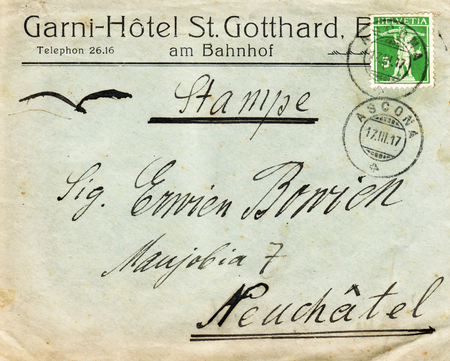

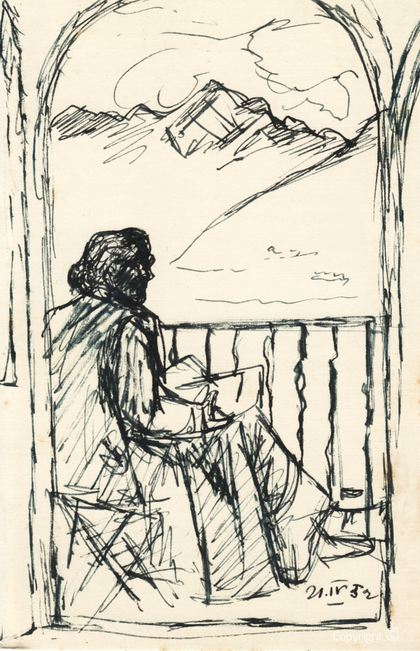

As the son of East Prussian parents, Erwin Bowien grew up with his sisters, Erika and Ursula, in Switzerland on Lake Neuchâtel, where he attended school in French at the Collège Latin and became a pan-European early on in his life. After the strict Schiller School in Berlin where he had spent his first years of secondary school, the school in Switzerland was a completely new atmosphere. Time and again Bowien insisted that the time at the Collège Latin was one of the happiest of his life. As a boy, then, Bowien learned the beautiful, pure French of Neuchâtel and acquired some of that Swiss character through his experiences there. His father Erich Bowien was a well-travelled architect and civil engineer and had found himself stuck in Switzerland on his way to North Africa, so he opened an East Asian art house in Zurich. Many visitors from India, China, and Japan stayed with Bowien's parents at Villa Maujobia N° 07, located halfway up the mountains overlooking Lake Neuchâtel. While there, Bowien received his first training in art in Professor Wiliam Racine's evening courses.

Erwin Bowien first signet as an artist. This was used in his pictures and drawings from 1917 to around 1924.

At the age of seventeen, he exhibited for the first time at the Rose d'Or gallery in Neuchâtel. The Swiss critics liked it so much that they gave the young man warm encouragement. Carl Russ-Suchard, the owner of the Suchard chocolate factory, became the young artist's first patron and acquired numerous paintings for his art collection. This idyll was suddenly interrupted by war and the time of the soldier.

After the loss of their Swiss citizenship, the family was expelled and settled in Weil am Rhein, just across the German border. Bowien's father became the commercial director of the up-and-coming Rhine harbour near Basel and built the home on Bühlstraße where Bowien's mother lived under his care until a few years before Bowien's own death. Erwin Bowien also died in this house.

Bowien in World War I

Bowien on the front in the Argonne Forest

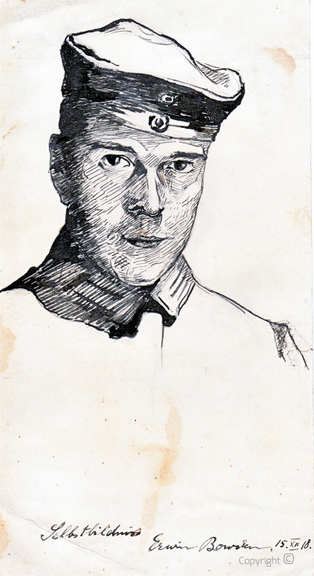

"…. For weeks now, I have been tormented by the thought of what might remain of me if I had to go to war as a German some day; because I never thought that I could avoid it.... But I could never get over why I lived if I stayed in the war...” On 3 September 1917, on his 18th birthday, Erwin Bowien was moved from his Swiss residence to the 15th Pioneer Battalion in Strasbourg, commanded by his father. Already in 1914, his father had been inducted as captain in the reserves and ended the war as a highly decorated major. He was one of the few to be awarded the "Pour le Mérite." After a difficult training, Bowien was the youngest person in the Army to be added to the Arendt Division thanks to his knowledge of French. This department worked in surveillance. Its section of the front stretched from Verdun through the Ardennes to Champagne. Its task was to listen in on French audio communications. During his time as a soldier on the Western Front, Bowien continued to pursue his passion by drawing and painting watercolours. His postcards from the field were always illustrated; among other things, he drew portraits of his comrades as well as the destroyed church in the village of Varenne. He also drew a bomb crater that was now covered in spring flowers. One of the most moving works the 18-year-old created during the war was his drawing of a grave cross in the Argonne Forest at night. He had happened upon the grave of his mother's brother, musicologist Dr Ernst Neufeldt, who had been killed at age of 34 during a French assault on 17 February 1915 near Vaugois. In 1918, Bowien showed some of his work at an exhibition organised by the Crown Prince Army Group in Charleville. He was demobilized in 1919 in Hanover. He would never mention nor wear the medal awarded him upon discharge. He then spent half a year at a camp for demobilized soldiers in Constance. He would always emphasise his disgust over war. A former student of his wrote: "... He was a friend of peace... as is well known, there was a right-wing or nationalist direction at the school, and we boys were always thrilled when our teachers told war stories during the final lesson before breaks. Mr. Bowien didn't like that and, instead, he read to us from Remarque's 'All Quiet on the Western Front.'"

About the artist

The artist Erwin Bowien, painter and essayist

Erwin Bowien's catalogue raisonné lists more than 2,800 extant works, but further works are still regularly discovered. In his oeuvre, pastel painting is equally ranked with his works in oil. It is the result of images made in many European countries over five decades of artistic creation as a restless painter and a man constantly drawing his world.

The early phase

The first phase of Erwin Bowien's work centres around the Lake Constance region. At the age of 19, he spent half a year as a demobilized soldier in a camp near Constance. He later worked as a probationary art teacher in Hechingen. This is where his first masterpiece was created: a portrait of a young man who had drowned in Lake Constance. The body is highlighted with a cobalt blue outline, while a greenish-grey shimmer covers the whole image. A colour choice that is characteristic of this creative phase marked by an impressionistic style and a slight melancholy. It was during this time that he met Hans Thoma: “… I spoke to Hans Thoma personally. As a twenty-year-old, he let me present my work to him, which he then examined with his piercing eyes. Thoma gave me a sketch on which he wrote a dedication ..."

A fateful encounter

Erwin Bowien was appointed Prussian civil servant as a drawing teacher at the Schwertstraße Secondary School in Solingen in 1925. This was the only phase of his life where he held down a "regular" job. In 1927, he met publisher Hanns Heinen and his wife Erna with whom he would have a lifelong friendship. The Heinen family became the centre of Erwin Bowien's life as a painter. Hanns Heinen, the head of the family, journalist, writer of poetry and prose, slim in stature (although heavier in later years), with light hair a consistently fresh face, ordinary rimless glasses, restrained gesture, a quiet voice, "actually," as he once said describing himself, "an idyllic man." As editor-in-chief of the local Solinger Tageblatt newspaper during the Third Reich, he was constantly confronted by those in power, for example for his highly respected, anti-regime editorial “The Rights of the Elderly,” his opposition to the party propaganda that “youth must be led by youth,” and a stage play entitled "Spartacus" which made his position clear for all to see. In one of his poems, he programmatically declared: "I am a socialist." His wife, Erna Johanna, née Mamms, was known as by family and close friends including Bowien as Amiéla, after Swiss philosopher and writer Henri Fréderic Amiél. Always free and open to each other. Thinking and observing as the essence of creativity. She refused to accept the Mother's Cross, to which she was entitled because she had four children. Her two sons: the elder Hanns who was much like his father and the younger Gunther, dark and solidly built, more like his mother. Gabriele, the older daughter, was a beautiful, very serious girl, friendly, intellectually active. Bettina, the redhead, was a whirlwind. She becames Bowien's master student. Heinen's old slate house near Solingen was a haven for culture. Artists from all over the Bergisches Land regularly met in the outstanding literary and artistic salons hosted by the lady of the house. She would recite her husband's poetry and moderate discussions about literature, art, and music; in other words, the house was overflowing with culture. Bowien met many artists there. His impressions of Indian writer Rabindranah Tagore remained with him for many years. At the heart of this family and this house remained an important spot throughout Bowien's life.

Bowien's exile in Holland

After a little over a decade of training including time with the internationally famous Art Nouveau painter Robert Engels, some time teaching (one of his students included Walter Scheel, future President of Germany), and numerous travels, Bowien began one of his most important creative phases: his years in Holland.

He spent a decade steering clear of the destructive spirit of National Socialism, working in Egmond, Camperduin, Alkmaar, and Hoorn in North Holland. He created a number of large pastels, depictions of dunes, beaches, the North Sea, and canals, as well as genre drawings dedicated to Dutch life and people. The works of this period are a study in grey-on-grey and reveal so many nuanced tones within that seeming uniform colour choice. The chalk paint often seems completely dematerialised.

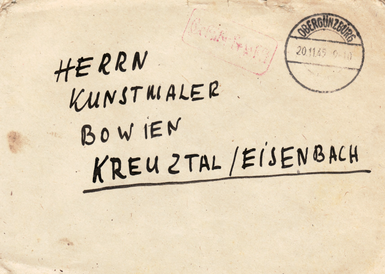

An escape across Germany

„… "At dawn on 10 May 1940, the bombs began to fall on Bergen airfield.... The aeroplanes circled in the air with the devil's sign and I had to tell the unsuspecting that this meant war ..." After the outbreak of war and the German invasion of the Netherlands, Bowien's days in his beloved North Holland were numbered. He knew it was only a matter of time before the German occupation authorities " would put him through his paces." He came up with a daring plan: "I requested permission to travel to Germany because my friend (Hanns Heinen) had sent an invitation to an exhibition in Solingen ... The Gestapo issued me a certificate stating that I could stay in Germany as long as I wanted." Bowien stayed until 1945! Since his passport had not been withdrawn, the German Army Office in Holland remained responsible for him as a German abroad, but could no longer locate him. The travel certificate had allowed Bowien to leave the occupied Netherlands legally, thus duping the authorities. A very dangerous game, because he still didn't have a valid military pass. An ID check with a demand for the military pass would have met his arrest. After a winter in a Solingen destined for destruction by bombing, Bowien travelled to Augsburg in 1943. "... So I came to friends in Augsburg in 1943, No, you don't have to report me to the police, I said every six weeks. I'm leaving soon, but then it became half a year, a very dangerous half a year." He knew he couldn't stay in one place too long. After half a year, he was denounced by a fellow painter. The Reich Chamber of Culture issued an arrest warrant for Erwin Bowien and the Gestapo confiscated twenty-five of his paintings. Visiting the Heinen family in Kreuzthal-Eisenbach, he was warned by the art dealer Vogl never to return to Augsburg. „… "The Gestapo confiscated twenty paintings... For me that was the signal to get moving... The money allowed me to spend one and a half years in remotest Allgäu..." But it was also dangerous there. On a short train ride to a neighbouring town, the worst possible thing almost happened: "… I sat with him (Hanns Heinen) for a while. Then I heard military certificates being asked for in the next compartment, so I said goodbye just in time. After this experience, I never again left Adelegg." “The third and bitterest test was the summons to join the Volkssturm. The chief physician of a pulmonary hospital (Haus Tanne) ... said: 'You can do military service.'Of course,' I replied, thankful not to be asked for my military papers. But there were no weapons left and so nothing happened except a few speeches. The panic would have destroyed me." The story of Erwin Bowien is the incredible story of a man who knew how to keep his honour and decency without compromise throughout the war.

Allgäu phase in hiding in Kreuzthal

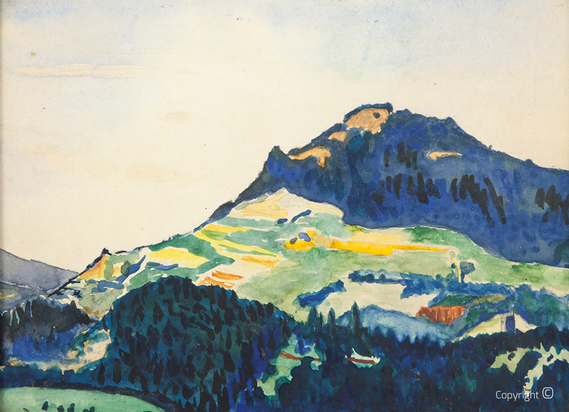

After he was forced to leave the vast landscapes of North Holland, Bowien discovered the world of the forest and mountains in his wartime hiding place in Kreuzthal in the Allgäu in southern Germany. This is where he spent almost two years as he waited out the end of the war. Tranquil landscape painting.

Kreuzthal – Eisenbach, a village at the end of the world in a narrow, cruciform valley somewhere in the Allgäu! This where painter Erwin Bowien, who had just spent ten years working painting the endless horizons and sand dunes of the North Sea and the canals of Holland, now spent two years in hiding. This was the calm before the storm where Bowien discovered a new world. The painter had to open himself up to a new landscape and a new experience. The blackness of a gorge, the silhouettes of the ridges, and the forest that separates the distance from the foreground everywhere you look were something an artist first perceives as threatening: “… From the heights above the valley, this forest is omni-present like a grid... It lends the landscape, which is so wide in itself, something uncanny..." After a long arduous ascent through the forest, having arrived at the ridge and finally seeing the breath-taking views of his beloved Switzerland, Bowien started to rave: "... In the background Säntis and Altmann solemnly look over the Pfänder and Tödi and Glärnisch are clearly visible further in the backdrop, as well as the Scesaplana and the Silvrettaspitze and, on the far left, the mountains above Obersdorf... If only this forest weren't here, standing like a barrier preventing my escape to freedom.” The artist now had lots of time to work not only with the motif of the forest, but also to observe the silhouettes of the mountains and to learn to love them. Would the trips he later took each year to paint in the Swiss and Bavarian mountains and the wild, rugged depictions of the mountainous landscapes of Norway have been conceivable without this time in Kreuzthal?

The artist colony in the "Black House" in Solingen

Der Lyriker und Schriftsteller Hanns Heinen (1895-1961) erwarb 1932 in der bergischen Stadt Solingen ein Fachwerkensemble bestehend aus zwei historischen Gebäuden. Im größeren der beiden, dem sogenannten „Schwarzen Haus“, entstand auf Betreiben der kunstsinnigen Hausherrin - Erna Heinen-Steinhoff (1898-1969), ein Literarischer Salon.

1945 zog - als erster Maler der sogenannten „Künstlerkolonie“ - der aus dem Exil wiederkehrende Künstler Erwin Johannes Bowien (1899-1972) dort ein. Dieses Haus mit dem kleinen Atelier nebenan, dem sogenannten „Roten Haus“, wurde fortan bis zur Mitte der 60er Jahre sein festes Domizil, von dem er aus das gesamte Bergische Land erwanderte und auf Leinwand bannte. Danach teilt Erwin Bowien sein Leben zwischen Solingen und Weil am Rhein auf; unzählige Reisen durch Deutschland mit dem Schaffensschwerpunkt: Darstellung des Rheinstromes von der Quelle bis zur Mündung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der großen rheinischen Kathedralen. Als ständig Reisender unternahm er aber auch ausgedehnte Reisen in die Schweiz und nach Norwegen.

Er entdecke das Talent seiner kleinen Mitbewohnerin, der Tochter des Hauses - Bettina Heinen-Ayech (1937-2020) - welche er ab 1950 systematisch zur Künstlerin ausbildete. Ab 1955 kam der Hamburger Künstler Amud Uwe Millies (1932-2008) hinzu und bezog als dritter und letzter Maler den Ort. In den Jahren 1969 bis 1971 lebte und arbeitete der Bildhauer Ernst Egon Osländer (1928-2015) im Anwesen.

On the move after the war

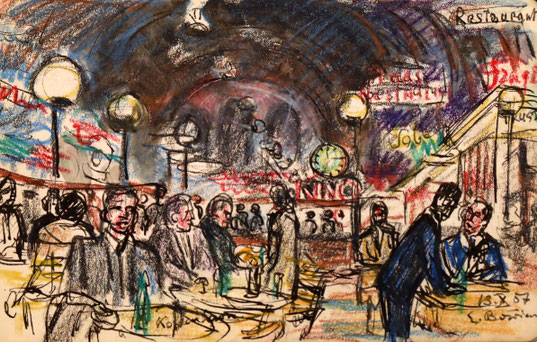

In the decade after the war, Bowien travelled a lot between Switzerland and Norway. Every year, he painted a cycle of Swiss cities in the Canton of Ticino, but it was especially his annual excursion to Norway, to Gjövik on Lake Mjösa and repeatedly to Sandnessjoen on the island of Alsten, where Bowien found "his" landscape in its purest form: a unique, primeval landscape that he captured with great precision. This is where the sense of measure that characterizes Bowien's late work first emerged.

Erwin Bowien's final signature as an artist. This was used continuously in his pictures and drawings from around 1925.

The great creative cycles of the last decade of his life: The representation of the Rhine from the source to the mouth as a European lifeline, the Norway cycle and the cycle of Swiss cities

The great creative cycle of his last decade was the depiction of the Rhine from its sources in the Alps to its estuaries in the North Sea. This topic was symbolic for an artist who embodied the European spirit. The motifs: architecturally piled-up landscapes and ever-dramatic cityscapes. This is when his important depictions of Rhineland cathedrals were created: six different views of Cologne Cathedral alone, but also Breisach, Freiburg, the cathedral churches of Worms and Speyer, the minsters of Strasbourg and Thann, and the many churches tucked among the vineyards of the Upper Rhine. The works from this period impress with their force, spontaneity, and peculiar composition and colour choices. Bowien described it as follows: "... and not since the Englishman Turner, who painted the Rhine from Cologne to Basel, has any painter been interested in the Rhine as a whole. For me, however, the legs of the Rhine reaching into Holland also belong as well as the wonderful stretch to Lake Constance and then from Lake Constance to the springs. It is incredibly beautiful..."

The great creative cycles of the last life ...

The Norway and Switzerland cycle

The painter as author, European before his time and universalist

Bowien was not only a painter, but also a philosopher, poet, and novelist who wrote his autobiography even though he was quite ill. The core of his literary legacy are the diaries he kept throughout his life, filled with reflections, poems, and dialogues. The most important is his 1944-45 diary written in French: "Les Heures perdues du Matin, Journal d'un Artiste peintre, Alpes Bavaroises 1944-45." There are Bowien manuscripts that remain unpublished: "The School of Dilettantes," a collection of novellas from the Dutch period, and "Worn Clothes," one of his books dedicated to his Swiss years, are both waiting to be edited and published.